Die Aufnahme dokumentiert eine morgendliche buddhistische Andacht im Goei-dō des Higashi Hongan-ji-Tempels in Kyōto am Morgen des 30.03.2025. Ich betrete die Tempelhalle und begebe mich wie die anderen Anwesenden in den Fersensitz (seiza, 正座) und schalte den Rekorder an. Die Aufnahme beginnt mit dem Ausrichten des Rekorders, auf meiner Tasche und dem bequemen Positionieren im Fersensitz. Der Raum wird „gesammelt“.

Die Aufnahme ist ca. 26 Minuten lang. Die Andacht begibt bei 2:48 mit vereinzelten Gong-/Metallschalenschlägen. Ein Mönch eröffnet mit einer kurzen Formel.

Aufnahme vom 30.03.2025 mit einem Sony PCM-M10, nachbearbeitet mit WaveLab Pro 12

Die Jōdo-Shinshū (浄土真宗, deutsch „Wahre Schule des Reinen Landes“), gegründet von Shinran Shōnin (1173-1263), ist eine der größten buddhistischen Schulen in Japan. Sie basiert auf dem Sukhāvatīvyūha-Sūtra (jap.: 阿弥陀経, Amida-kyō), dem Sūtra des Landes der Glückseligkeit. Sie ist dem Amidismus zugehörig. Im Zentrum ihrer Lehre steht das Vertrauen in den transzendenten Buddha Amitabha (jap.: 阿弥陀 Amida) und die Hoffnung auf eine Wiedergeburt in seinem „Reinen Land“ (jōdo 浄土).

Die Jōdo-Shinshū-Liturgie ist schlicht und fokussiert: keine komplexen Mantra-Rezitationen wie im Shingon-Buddhismus, keine ritualmagischen Elemente, keine rhythmische Begleitung, kein Trommeln, keine Verwendung des mokugyō (Holzfisch), kein dramatischer Singsang, keine komplizierten Sutren-Melodien, sondern ruhige, gemeinsame Rezitation als Ausdruck von Dankbarkeit, Vertrauen und Verbundenheit mit Amida.

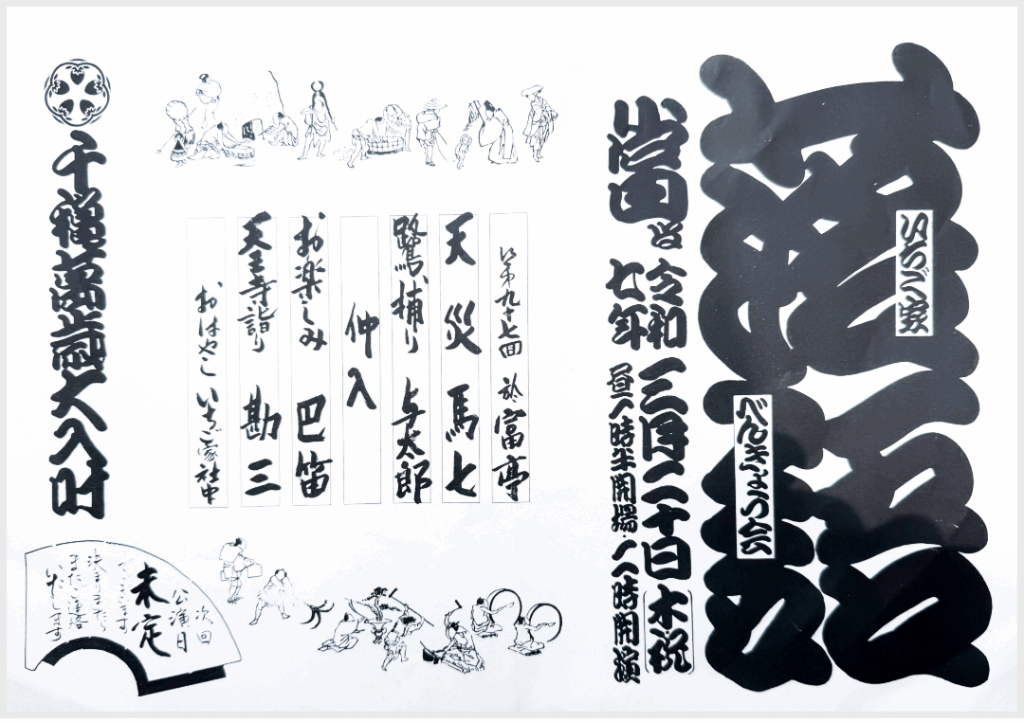

Die Kernelemente der Jōdo-Shinshū-Liturgie sind das:

1. Shōshinge (正信偈), „Hymne des wahren Glaubens“

2. Wasan (和讃), Hymnen Shinrans

3. Nembutsu (南無阿弥陀仏), Namu Amida Butsu („Verehrung dem Buddha Amida“)

Der zweite Teil der Aufnahme beginnt direkt mit den gesprochenen Worten eines Mönches, wahrscheinlich ein kurzer höflicher Dankessatz, der das Ende der Einheit des kollektiven Chanting-Blocks im Jōdo-Shinshū markiert. Es folgt eine Pause (bis ca. 1:26), danach beginnt ein Mönch mit einer „Shōmyō“-artigen Solorezitation.

Aufnahme vom 30.03.2025 mit einem Sony PCM-M10, nachbearbeitet mit WaveLab Pro 12

Hier handelt es sich wahrscheinlich um eine kurze Einzelhommage – Dokyō (独経) – für Amida, eine „Einzel-Sutrarezitation“. Der Mönch trägt allein einen kurzen Abschnitt eines Sutras vor, z.B. das Sanbutsuge (讃仏偈)) oder hier (sehr wahrscheinlich) das Jūji-hōgo (重誓偈).

Etwas ausführlichere Erläuterungen finden sich in dem folgenden fünfseitigen Dokument: